"Bicycle Kick" from the short story collection HIDING OUT

It’s all because of my poor reflexes. A case of having little physical skill, sure, and maybe a short attention span. But there I was, hungover on a Sunday morning, in one of those indoor sports facilities that you never think you’ll see the inside of, with the walled soccer fields and artificial turf like hot steel wool. Huge pictures of athletes you’ve never heard of adorn the walls, tricking you into thinking you look like them. But you don’t, you look like me; tired and still not entirely clear on why you’re playing in this league, some five games into the season. Unshaven, unenthusiastic, nearly undead. My headache, the one from the hangover, had me running in zig zags. Every time I turned I would flinch and my body would lurch in another direction. So it wasn’t a surprise, in retrospect. It took me off-guard, but I should have known it would happen.

There was a guy on the other team wearing the Brazil national team jersey—it didn’t even say Ronaldo on the back—it was some obscure player I found out later, the guy was such a fan. But for a moment, I stared at the back of his jersey, at the name, Azofeifa. Such a name, Azofeifa. Beats the name on the back of my T-shirt, Terry. I was staring at the name Azofeifa, wondering if this guy, Azofeifa, if he could possibly be a member of the Brazilian team, his shorts blue and new enough, his socks pulled high enough. And as I was thinking this, just watching him, Azofeifa—such a name!—wondering if I was in the presence of greatness and playing against a World Cup competitor, as this thought crossed my mind I saw the ball emerge, in the air, in my peripheral vision, and I saw Azofeifa take two confident strides away from me and then, something magical happened—and I’d like for you to understand the magic of it before I tell you the consequences, because the magic is the best part—Azofeifa took two confident strides away from me, and as the ball knuckled through the air, no spin at all, just a flat and boring thing, I watched Azofeifa leap, his left leg kicking in front of him like a ballerina, and I noticed that his thigh muscle, I believe it’s called a quadriceps, was of such girth and animal litheness that I quivered, but then, his torso realigned, so it looked like he was reclining in the air, parallel to the ground, just buffeted by the wind, gravity at the whim of Azofeifa, and as his left leg hastened back down he lifted his right so that it emerged above him, an obtuse angle on the Azofeifa plane, and again with the suppleness of the quad, and the kick, connecting with the ball and sending this object, appearing two-dimensional before he touched it but now, in Azofeifa’s universe it was a living thing, spinning with a celestial speed and growing larger by the second, it could only be described as magic, this bicycle kick that defied physical laws in a most real way, and the ball now coming alive and growing so large that it was there, in front of my face, and here we see the consequences of my momentary obsession with Azofeifa, my reflexes so poor, my headache so monstrous, my fleeting love for Azofeifa so pure, that I couldn’t even shutter my eyelids, and the ball hit my bare yellow eyeball and it is here, of course, that I stop remembering.

I tell you this because it explains just how important Azofeifa is to my current condition, both physical and mental. My team, acquaintances from work and their friends and some other people I would never associate with if I actually associated, rushed me to the hospital. I came to in the emergency room, waking up stuck to a vinyl chair, surrounded by coughing and bleeding people sensibly dressed in winter parkas and boots. I in my indoor track shoes, Umbro shorts and ratty T-shirt with my name on the back. It was quite a shock, and I yelped a bit, which I think got me in to see the doctor quicker than even the guy both shivering and sweating, who looked like his skin was possibly falling off. I looked so bad on account of the hangover and the bare eyeball contact that this man nodded at me to go past. The doctor, a quack, I’m sure, calling himself Dr. Owen and not telling me if that was his first or last name so I couldn’t know if he was being cute or not, said I was probably fine, which I knew. But, he said, it would be important to take a CAT scan, an expensive procedure that my insurance would largely cover and would ensure that there wasn’t any hemorrhaging anywhere, that my retina was intact, and that various other side effects of being smashed in the bare eyeball were not in effect. I agreed.

I fell asleep in the CAT scan, which I don’t think you’re supposed to do, especially if you might have a concussion, as I might have had, but Dr. Owen didn’t notice. When it was through, I sat in a station just off the nurse’s desk, where I could watch them mark and erase names on a giant whiteboard. Every erasure brought with it an anxiety. I had to listen hard to ensure it wasn’t because someone had died, that the patients here were just being dispatched, but not to the grave. Someone down the hall in Bed 8 was labeled Knife Shoulder. I saw my name under Bed 3—Soccer Head, it read. I liked that. I noticed that in Bed 11, listed on the chart just below mine, it read Baby Trauma, and I decided to stop reading. My right eye was bandaged, and I made a game of pressing down around the socket, to determine where it hurt most. I wondered where my teammates were. A few of them had been beside me when I’d awakened and yelped, but they didn’t follow me into the scan. I decided not to ask the nurses to fetch them.

Dr. Owen arrived after a long time, long enough to make me think I’d been forgotten, Soccer Head in Bed 3 now so permanent on the whiteboard they’d have to use vinegar to wipe me out. The doctor was tall in a 19th-century way, slightly stooped and with glasses just slightly larger than his eyes. A white idea of a beard played along his chin, wispy and ugly.

“I have good news and I have bad news,” he told me. “And the bad news is more complicated, so I’m going to give you the good news first.”

This seemed to me a fair deal.

“The good news is that you don’t have a concussion, and other than a weird-looking shiner, on account of your eye being open on impact, no major damage at all.”

This was good news. I was happy my head had made it out OK. Dr. Owen started in on the bad news. The CAT Scan had shown I had an unusual condition in my head. Two aneurysms, side-by-side. Two bloated blood vessels that could, given enough emotional or physical stress, burst, sending squid clouds of blood over my brain, erasing thoughts, functions, memories—irreparable damage. Highly unusual, to have two such advanced aneurysms so close together, he assured me, as if I should be proud. Like I was up for the Guinness Book.

“Normally, if we had caught one aneurysm, I’d say we should open up your head and get it out,” he said. “It’s not an easy procedure, but it’s safer than walking around with a time bomb up there. But if we did that in your case, we’d be in danger of rupturing the second aneurysm, and the whole procedure would be for naught.”

I closed my left eye, but kept my right one, behind the bandage, open. I liked the fuzzy darkness. It built an incomprehensible wall around my head that kept me from concentrating.

“Do you want to see the scan?” Doctor Own asked.

“No, I don’t wanna—why would I wanna—I don’t,” I said.

“OK,” he said. “But in case you’re curious, it looks like two snakes swallowed rabbits then crawled inside your head.”

I heard him pick up the scan, but I kept my left eye shut so I wouldn’t have to see it.

“Suit yourself,” Dr. Owen said, obviously disappointed.

I wasn’t quite clear on what he was telling me, and it annoyed me that I had to ask.

“So am I the walking dead, then?” I asked. “How many months?”

“Well, no one can really tell you that. These things, people die of natural causes with them still intact, still in their heads. Others rupture at any moment; anything can do it, really. You could live the rest of your natural life as well as anyone else, or you could take two steps away from me and fall to your death.”

It was no help, precisely zero information. The news had emptied me and Dr. Owen gave me nothing to fill that space. He just stared off down the corridor, like he was marking the moment I’d drop.

“Will I have any side effects, any dizziness or blindness or headaches?”

“Nothing’s for sure. You’ll likely get headaches, but do you get headaches now?”

I said I did.

“Then you won’t notice a difference.”

“What about loss of memory, paralysis—should I stop drinking?”

He told me that I didn’t have to worry about those, that I should cut back on the drinking, and that he would prescribe a blood thinner for me.

“So there are no ill effects?” I asked.

“Well, as I said, you could die.”

I looked him in the eye, my one good eye flicking back and forth between the two of his.

“So, if you had to give me odds for living another forty years, say until I was 70, what would the odds be?”

“I’m not very good at that sort of thing.”

“10 to 1? 100 to 1?”

“I’ve never really understood what that means,” he said.

“Just give me the odds.”

“Of you living till you’re 70?” he said. “I’d say it’s 35-75.”

I shook my head. Dr. Owen and his nineteenth-century frame, blunt disregard for my need to be reassured and fucked-up math was too much. This man was making my world small. I imagined he was a moon who had just eclipsed me.

I walked into the waiting room and saw that the team had left. I walked out onto the sidewalk and stared at the sun, out of my one good eye. I imagined Azofeifa, so fleet and at ease in his body. My feet felt magnetized, drawn to the core of the earth, leaden. I tried to imagine that gravity was pulling my blood down, sucking it back out of the swollen ice-purple bruise around my right eye, out of the one aneurysm, and then out of the other. Things moved inside me, as I stood still, my feet pulling down.

At the bar, later that afternoon, with the team all still wearing their T-shirts and all buying me beer after beer and slapping me in the shoulder once they got drunk enough to stop treating me like porcelain, with everyone there with their names across their backs exalting at having gotten out of the game before they lost, thanks to my eye injury, I couldn’t decide if I should tell them. It’s not really a topic for bar conversation, or that’s exactly what it is, but not this type of bar conversation. I wanted to sit down with somebody, didn’t matter who, sit down across from each other at a table not too far from the jukebox, and sip a beer and tell them that it could be the last beer of my life, or it could be just another, I would never know. And the whole thing made me feel stupid, like I was writing a poem for a high school literary magazine. I’d think it was important and deep but the grammar would be all wrong and adults would secretly laugh at me. I wanted to change the name on the back of my T-shirt, or I wanted to keep it exactly the same but be somewhere where no one knew it, or I wanted the people who surrounded me in the bar to remember it without having to secretly lean back and read it, or I wanted to be Azofeifa, spin off into the Azofeifa orbit, free in a different way. I stood up from my bar stool and planted my feet on the floor, the magnets returning, draining that blood out of my brain, the aneurysms thinning, the rabbits emerging whole from the snakes’ mouths and bicycle kicking, their little rabbit feet flipping through the air. I closed my good eye and opened my bad one and stared out into the fuzzy darkness around me, the atmospheric wall built by me, built out of my slow reflexes, my brief and weird obsessions, my inability to react, and I wondered what I would do next.

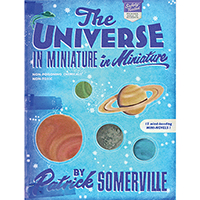

Other books you might enjoy